When I began Gurp, my primary criterion was “must do everything my current Ansible setup does”. With a successful, hands-free rebuild of all my zones, this goal is achieved, and I’m cutting release 1.0.0.

Let’s have a look at some charts. I love charts. Gurp has a --metrics-to

option, which makes it push run summary metrics to my VictoriaMetrics instance,

in InfluxDB format.

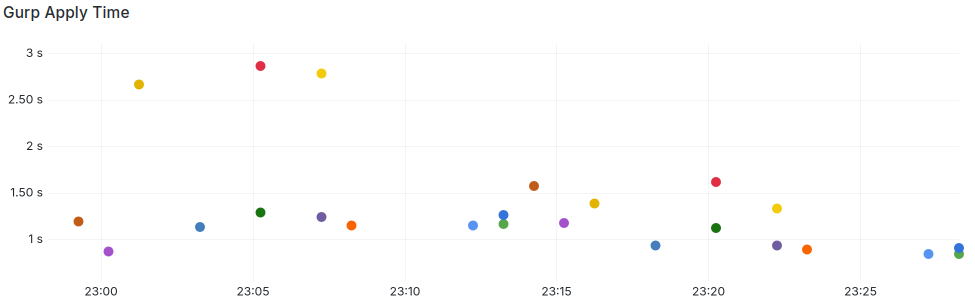

Here’s the apply time. In all but one of these zones Gurp is managing somewhere between thirty and a hundred and twenty resources. (The exception is the blue dots - an LX zone with ten resources whose state is asserted in about a hundred milliseconds.)

The green outlier is a global zone which inspects a large number of ZFS

filesystems. As a rule, most of Gurp’s run time is calling pkg or gem. If it

doesn’t have to do that Gurp can fire up, compile your machine definition and

assert (and possibly correct) the state of dozens of resources in well under a

second. When I maintained these same configs with Puppet, it was taking at least

a couple of minutes per zone. Ansible was worse. Gurp can do thirty zones in

thirty seconds.

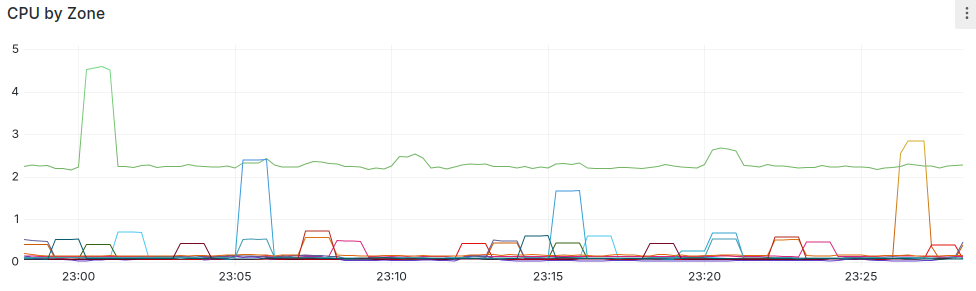

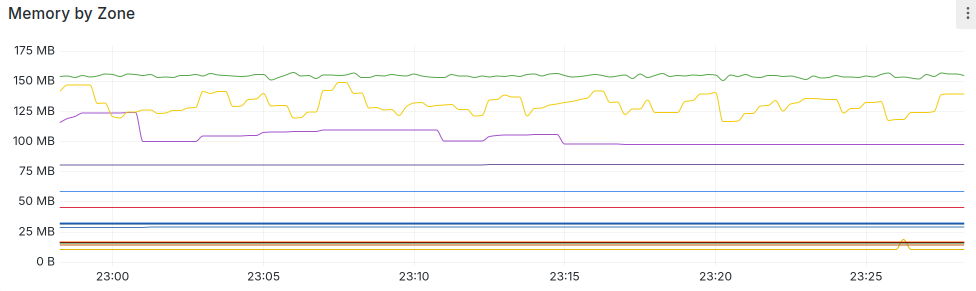

How about resource usage? Ansible runs maxed out the CPU on my box, and Chef used so much memory most of my zones wouldn’t let it run.

That’s percentage CPU (I need to fix that axis), and none of the spikes correlate with Gurp runs. How about memory?

Flat. You can’t see Gurp at all.

What I Got Right

-

Janet Config. The more config I describe with my Janet DSL, the more I like it. It’s clear and simple, and it’s so easy to write modules that I started doing it without even realising.

I have fewer problems with malformed Janet than I used to have with YAML. I use Helix with janet-lsp, so it’s easy to spot mismatched parens, and if any slip through, Janet (and therefore Gurp) gives you pretty helpful errors. I also have Spork installed on my dev box, which gives Helix a

:fmtcommand that makes Janet look lovely. Lisp may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I like it.And as a side-effect of writing Gurp, Janet now officially supports illumos.

-

No variable/attribute hierarchy. Chef et al have complicated ways of automatically inheriting variables. I chose to not do this at all, and make the user fetch things with Janet. In my environment, this is enough. I have a

globals.janetfile containing a bunch of(def)s, all using an appropriate data structure. My modules(import)this, and(get)value. It couldn’t be clearer. -

Acceptance testing with Judge. I like this approach so much I’m thinking about spinning off a proper compliance tool.

-

Keeping it Simple. If I had tried to cover everything I could think of, rather than everything I need, I’d probably still be writing the

pkgdoer.Gurp has been a spare-time project, A couple of hours after work, a few hours on a Sunday evening, that kind of thing. It’s been about four months from first commit to 1.0.0, and I that’s not bad. I think using Rust helped with that. I feel like it helps me get a lot done quickly.

What I Got Wrong

-

Janet -> Rust. I wasted far too much time parsing

Janetobjects with Rust. Using JSON as an interchange format between front and back made life so much easier. -

References. I put quite a bit of effort into allowing Gurp resources to reference properties of other resources, and I never use it. It’s cleaner and easier to stick a

(def)at the top of the file and refer to it in both places. -

Focusing on being “correct”. “Global mutable state” might be as dirty a string of words as programming has, but using it in the Janet front-end allowed me to throw out a stack of over-complicated and flaky semi-functional experiments and helper macros, and simply get the job done. Maybe it’s a shame Janet doesn’t have something like Clojure’s

atomto sweeten the pill, but in a single-threaded one-and-done process, I don’t even need that. -

Focusing on speed. I made horrible and oversimplified doers by trying to minimise my calls to

pkg,pkginandgem. Much of that horribleness is still there, but with more on top to get around the limitations of the original decisions. Truth is, there’s no way to get around how long these external tools take, but it still galls me that my lovely fast program stops dead whilepkgbreaks out the Python. -

Caching.For instance: When the

zonedoer runs, it callszoneadmto get a list of current zones, and puts it in alazy_static(). Fine, right? That’s a potentially expensive-ish operation. And it works fine, until, that is, you write a test that creates dataset and a zone, delegates the former to the latter, bootstraps, then cleans up, and you get an error saying the dataset is still in use. Then you re-run the test, and it works fine. Yes. That’s because the first time the zone didn’t exist, and Gurp cached that state. So when it came to remove the zone, it hit the cache, found the zone didn’t exist, so it didn’t need to remove it. And, indeed, the dataset is still in use, because the zone is still running a service that uses it. There’s very little caching in Gurp now. -

Trusting LLMs. I thought it would be interesting to “pair” with an LLM on this project. Maybe it’s my choice of target OS and language, but the results were generally awful. Any questions on Janet get a completely made-up answer. Made up code with made-up functions and, almost always, Clojure syntax. It’s easy to prove the model is wrong with code. It doesn’t compile, or it gives the wrong output: you waste time, but it isn’t dangerous. It turned out the softer, more general Lisp guidance was worse. I took an LLM’s advice on a general approach in the front-end, which made a bug that sat unnoticed for weeks, and only got dug out when I wrote my full functional test suite. tl;dr resources in certain Janet structures never got applied, and never produced an error. I should have known better, but these things can be terribly persuasive.

The Rust story is more mixed. I’m still very much a Rust developer-in-progress, and I find the LLMs useful in explaining exactly why something doesn’t compile, or to step through something I don’t quite understand, or for advice on idioms. Sometimes it’s wrong, but often it’s right enough to be useful. I asked it to write me a Janet->JSON converter, and it was near enough that ten minutes fettling had it working. I got it to write tests for me, but the tests were never particularly good. I gave it functions I knew could be more Rust-ish and asked it to refactor. Sometimes I learned something about Rust, but more often I got back something that was more complicated and didn’t compile. Attempts to DRY up code always led down a path of traits, enums, and generics, with the LLM hopelessly tying itself (and me) up in knots in no time, each failure making something more complicated and more broken. It’s like the junior dev whose solution to every problem is to add add more code.

The biggest disappointment, having had friends report remarkable results with them, was giving the messy MVP codebase to an agent. I gave it clear instructions on improving the quality of the code, and left it grinding for hours. I got back a branch full of broken junk. When I tried a different agent and a different LLM, I got back almost exactly what I’d given it, but it didn’t compile any more.

My strongest conclusion from “vibe coding” or whatever it’s supposed to be is that these things are nearly always some degree of wrong. This is not so bad in our walled garden, where a compiler or test can quickly prove or disprove an answer: all we have to lose is some time. But I’ve no reason to think LLMs are any more accurate when people ask them for legal, moral, or medical advice. Yet it seems half the world takes whatever the things spout out as fact, and that bothers me.

What I’m Still Not Sure About

-

Not having a generic doer. I very nearly put this in the first section, because, today, I still like the idea that Gurp will not let you run an arbitrary command. It’s safer, it lets you do more reasonable no-op planning, and it means that important operations (i.e. anything you want to do to a live system) requires some thought and testing. It makes everything “official”. I realise this would limit adoption, but as I have no ambition or expectation for anyone beyond myself to run Gurp; that’s fine.

-

Explicit Dependencies. So far I have not needed any explicit

beforeoraftertype markers. Just having Gurp do resource types in a particular order has been enough. But, again, there’s something at the back of my head telling me I’ll need it one day. -

Secrets. Anything involving secrets gets complicated fast, and avoiding complexity has been my top priority on Gurp. I have a

gurp-configGit repo which contains all my host, role, and module definitions, and the aforementionedglobals.janet. The modules that need to also includesecrets.janet, which is outside the repo and not under version control at all. As it’s just a plain text file, I obviously wouldn’t recommend that approach for any real situation, but it’s fine in my home lab, and that’s the itch I need to scratch. Gurp has the wherewithal to use some CLI tool like SOPS to decrypt secrets, but runninggurp compile --format=jsonwould expose them as plaintext. There’s never a nice way to solve any secrets problem and, given I don’t have anything which really needs to be secret, I’m not in a rush to tackle it.

What Next

The whole codebase could probably use a refactor. So many changes of plan have left vestigial tails everywhere, and some of the Janet is proper spaghetti. I’ve got good test coverage for the front-end, so refactoring that ought not to be too risky, and I always feel very safe refactoring Rust.

My initial approach tried to make the doers quite generic, and this led to messy and indirect code. That’s nearly all gone now. Tightly focused doers are half the size and easier to understand.

There’s a branch with bhyve zone support, but I’m a bit ambivalent about it.

It was one thing adding LX support, but bhyve, with cloud-init is a lot

messier, and Gurp offers no way whatsoever to configure a “real” Linux or BSD

instance. Gurping an Unbuntu bhyve zone means you need Puppet or something to

configure it, and that feels like it makes this whole exercise a bit pointless.

As I mentioned when

I wrote about bootstrapping zones, I have a rough

idea about client-server Gurp. A central instance would have access to all your

files and configs, and clients would request their data from it. The first step

would be to make file’s :from accept URIs, which would be useful anyway. The

question is, would the client or the server compile the Janet? If the former,

you would only have to get the compiled JSON data, but you couldn’t have any

host-specific logic in your front-end code, because you’d be inspecting the

server. (I don’t do this at all, but I can easily see cases where it would make

sense.) If the latter, you’ve likely got to pull a whole load of files down and

assemble them somehow. Offering both probably puts you in some sort of awful,

confusing compromise, like pull-mode Ansible. And once you start doing HTTP,

you’ve got to do HTTPS, and then we’re in the world of certificates, and we’re

back to secrets management, and I really don’t think I can be bothered with it.

I’ve covered most of illumos’s OS primitives, but few in depth. Some doers, particularly those which handle packages, are as limited as they can be. Then there are fundamental things Gurp simply can’t do, like selecting package mediators, or configuring network interfaces. So there’s plenty of room for improvement and plenty of scope for new features. But as of this moment, I’m not sure how much of this I want to take on. I wanted to see if I could replicate my Ansible usage with Rust and Janet, and I could. That might be enough for a little while.